Our Nature of Death – The Nature of our World

This world is characterized by falling away. Everyday we get closer to that day of inevitability. Every day is a final goodbye to our loved ones, but we realize it not. And when that day of departure finally arrives, those final goodbyes suddenly become realized. Each goodbye, each farewell, carries within it the sadness of separation. This world is therefore impregnated with that sadness, that great undercurrent of tragedy. It is an integral part of what it means to truly be human, forming as part of the edifice of our Being. If we forget death, then we forget sadness, and when we forget sadness, we forget compassion and the sensitivity of heart. We forget our nature. But this sensitivity of heart is made as such only by virtue of the knowledge of death, for it is what causes us to discern by means of comparison the sacredness of life. Knowledge of the sacredness of life makes us sensitive to it, and so it can be said that this impermanent world of vanishing forms is the instrument by which we learn about the sacred through the modality of human experience. The Islamic path is ultimately the path of becoming more human by returning to the fitra [فطرة – Nature]. If we deny the existence of human nature, we are effectively denying the existence of the sacred. And when we deny the existence of the sacred, then we become desacralized.

“Die before you die.”

[Attribution] The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

And so it is said by the Holy Prophet ﷺ that the masses will become worthless on account of al-wahn, a concept that denotes attachment, clinging, infatuation, and obsessive lust for the dunya [دُنْيا – illusory world] and fearful hatred and ignorance of death. When we can neither see beyond this world nor intuit beyond our [base] desire[s] for it, our intellect becomes obscured by a veil. We begin to covet the world all the more deeply believing it to be all that there is. We develop a sense of entitlement, and this entitlement forms the edifice of our philosophies and ethics. We cannot help but become invested in a thing when we believe our existence is dependent on it, even if we identify with religious doctrine that says otherwise; in this case, religion becomes mere sacrilegious pageantry, unserious about the great affair that is our life’s quest. But then this represents the secularization of religion into a mere cultural identity since it has been denied its sacred nature. Adherence in this manner is empty and void, and merely makes the intellect all the more deficient. Sincere religion is not about identity, that clothing that the ego wears in order to define itself. Rather, it is about what you are willing to surrender before God in order to traverse the great abyss that awaits us in the afterlife. What you cannot sacrifice, you become a slave to. And what you become a slave to, in turn, becomes the Lord that governs your Heart. The Islamic path is said to be the path of submission, and there is nothing more precious to the human being than its own sense of will, for the will is the modality of Becoming. But under the ego, the will of man becomes a force of further atomization, further constriction, further imprisonment. The path of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ is thus said to be the path of thorns because one must be willing to shed all that one clings to of this world, even one’s own sense of will, which has become entangled in it. But in doing so one is transformed, taken from a constricted state of egoic-consciousness that is always wandering, searching, and hunting, grasping at something that is just always out of reach, to the emancipation into God Consciousness, which is a state of rectification and contentment. As Shaykh Abdal Hakim Murad explains, as the veils of the false self are lifted, then the distinction between the will of man and the will of God becomes all but an illusion, a veil that is lifted.

Meditation of the Divine Statement

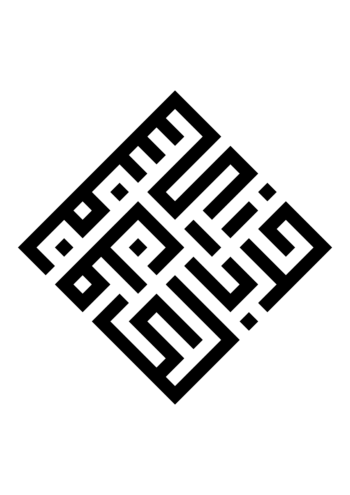

أشهدُ أنْ لا إلهَ إلاَّ اللهُ

I bear witness that there is no god [nothing worthy of worship] Except Allāh [God]

The Divine Statement opens the door of the heart, to meditate upon it is to travel inwardly into the inner realities of Being. But this requires the painful dissolution of the false self, which is formed out of the intricate pattern of our conceptual attachments and their consequential identities. But in their dissolution, the mind becomes totally silent. And in the silence of the mind, there is an expansion of consciousness into the depths of one’s Being. This is to say that the Heart is expanding, overtaking one’s awareness. It is in this realm that Truth, which is totally inexplicable, may flash and the lights of the Divine apprehended upon the mirror of the heart.

This rendition was composed for my father, but he had passed away before I could complete it. Its aesthetic was meant to convey the heaviness of the statement and the profundity of the inward journey of the nafs [نَفْس – soul or self]. The chanting of the Divine Statement remains largely fixed in terms of its intonation range, like an unmoving center, an axiom, absolute in its intensity like the depths of the ocean’s undercurrent. However, the overlaying ambience ranges more widely in its intonation, frequency, and depth, as if painting and giving a variety of shapes and colors to that underlying abstract principle in the form of emotional spectrums that otherwise lay dormant within it, hidden except to deeper human perception and experience. They are like the waves that we see on the surface of the ocean, which tells us something about the might of the undercurrent. From this perspective, it could be said that we as conscious creatures are not but the myriad variety of expressions of the Divine Statement.

I [God] am indeed with the brokenhearted

It was only after I had turned to it as part of my own meditative practice in order to process the tragic and painful circumstances of my father’s death that the dimension of sadness, grief, and loss were revealed as an essential experience of the Divine Statement, and therefore, what it means to travel the spiritual path. But at the same time, there is beauty in it because there is also a joy that is truly fundamental. There is a sweetness in the bitterness, and the lesson here is that despite how painful the world can be, there is always a way through it back to that unchanging center. We can navigate the spectrum of human experience back home by orienting ourselves around the Divine Axiom through the remembrance of Allāh. This is the resilience of the spirit, rooted in the revelatory guidance that conveys the reality of Allāh as the unmoving Divine Principle at the center of experience. It remains after the vicissitudes of impermanence subside. Even as it seems that only pain is left in its quake, it is possible to attain a hidden treasure beneath the rubble of the broken heart. Before and after it, the Divine Principle remains in the present, as the present moment of experience.

The world, by its nature, is vanishing. Vanishing is its perpetual state. When we are attached to it, then the world appears to us as the dunya [دُنْيا – illusory world], a word which is said to denote grapes that are just always beyond one’s grasp. Our internal state, characterized by the permanent perception of forms, defines our concept of the world which is then projected as the object of experience. And so our experience becomes characterized by attachment and [base] desire, chasing but never arriving. The material world, by virtue of its contingent nature, is always changing, always transforming, always transitioning, and so there is always loss by necessity because the prior state must by principle give way to the latter state; the present lives by virtue of the past dying. To move forward in time means to perpetually die, to let the past fall into oblivion. This perpetual movement towards the completion of our lives is a cycle of rebirths and deaths of the moment. But when our Being is characterized by attachment, our movement through this process is marked by tension. Desperately trying to cling to the moment, we try to prevent it from dying. But in attempting this impossible task, all we do is prevent ourselves from truly living with presence, for time never stops for anyone. Life from the moment of conception begins to dwindle away. That is our nature. To deny this is to deny our nature. To act in this way is to act contrary to nature.

By the nature of time;

Truly humanity is in a state of loss;

Except those who have faith and do good, who enjoin Truth and enjoin patience

However, the Divine Principle remains fixed at the center of it all, unchanging, unmoving. It represents the universal essence around which all particularity revolves. The Divine Statement is an expression of the First Principle of existence, and so everything in existence proceeds from it and everything returns to it. It [the Divine Statement] is therefore the essence of Ibada [عبادة – worship] as the process of returning to Oneness. Everything in existence revolves around it, and thus, it is capable of organizing all of the experiences, both the bitter and the sweet, that make up our world.

And He it is who grants life and deals death; and to Him is due the alternation of night and day.

Our existence is merely a borrowed quality from God, who alone is The Real, The Eternal, The Permanent, The Self-Existent. Even as phenomenal thought arises and ceases, we remain, both before thought and after thought. The closer we are in terms of proximal consciousness to God, the more we partake in The Real, and thus the more intense our existence as a matter of conscious presence is. An intense conscious presence naturally resists the chaotic fluctuations of impermanence, we neither become swept into the ocean of uncertainty nor into the darkness of unconsciousness and compulsiveness.

What we see as loss may be understood now as the transition from one expression of Divine Will to another, from one realm of existence to another, and so when we are grounded in the Divine Principle at the center of experience then we abide within the present moment, unceasing, unchanging, eternal. We are no longer caught in between our perception of the past and our perception of the future, trapped in regret and fear; whereas ego-consciousness is in constant flux, arising and ceasing, affixed to one impulse until it perishes and then to another, God Consciousness is all abiding. And thus, past and future vanish in the ocean of the present moment. This is to live in a state of effortlessness. This is to be in a state of hudur [حضور – presence] rather than a state of ghafla [غفلة – distraction, forgetfulness, inattentiveness]. And so we become the ibn/bint al-waqt [son/daughter of the moment].

To Die – The Negation of Illusion

أشهدُ أنْ لا إلهَ

I bear witness that there is no god [nothing worthy of worship]

Death is the ultimate expression of the Divine Statement, the final prostration to God. It is for one’s forehead to never again be lifted from the face of the Earth, but it is also for one’s consciousness to leave behind the Earthen body and proceed forth from the point of prostration [forehead] into the eternal.

“The death of one’s father breaks one’s back.”

Imam ‘Ali [كرم الله وجهه]

Performing the ghusl [غسل – ritual washing] of my father before his burial was a visceral reminder about the true nature of this world, about our true nature. As he lay before me on the cold steel table that rainy day in the mosque backroom, eyes forever closed, body cold, stiffened by rigor mortis, it was as if he was saying to me “Oh my son, this is the true reality of this world. Do not forget so that you are not deceived by it.” A final parting gift from him, a final wisdom from father to son before the coffin was closed over him, his face never to be seen again by my eyes. The seconds I had left with him depleted with great haste, they could not be held on to despite the desperate desire for nothing else. There is a profound sense of powerlessness felt here, perhaps only here where the pain overwhelms you. In this very painful reminder, all irrelevant matters to the soul were at once dropped, negated, forgotten, severed. Life is so very short, and to fill it with mere distraction, both in action as well as in thought, is self-destruction. Socrates had stated that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” These words have never felt any more true than at this moment. There is no experience more powerful than that of meditating on impermanence when it is clearly demonstrated in the passing away of one’s loved ones. It is one thing to practice it while they are alive, but to do so after witnessing their death grants a far greater apprehension. With this greater apprehension, there is greater experience. With greater experience, there is greater realization. With greater realization, there is greater pain and grief, but also understanding and therefore greater possibility of detachment and letting go of all that which imprisons the heart, as well as emerging on the other side and finding that hidden wisdom of our teleology.

“What am I to this world, and what is the world to me? My likeness in this world is that of a traveler who had taken rest beneath a tree, and who has thus gone forth from it, leaving it behind.”

The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

The key to attaining detachment from the world is by existentially negating it through the witnessing of its impermanent nature. By perceiving its impermanent nature, we can see its contingent nature. By nature of contingency, it lacks self-existence. Lacking self-existence, we can see how the existence of the world is merely a borrowed quality that partakes in the universal, which is self-existent. With existence being a borrowed quality, the world therefore lacks inherent reality. This observation pertains to our objective judgement of it, and as a judgement, directs our personal relationship with it. Continuing this thought sequencing, lacking inherent reality, the world lacks inherent value. Lacking inherent value, it lacks inherent meaning. And thus the conceptual objects of the world that we unconsciously place existential value on and that we chase as our will to meaning, to use Frankl’s term that describes the drive of human nature, dissolves under the gaze of the intellect. The allures of this world lose their luster, no longer impressive, they appear as mere bombast and pageantry. Wealth and status, mere circusry. Our will to meaning finally becomes divorced from the ego driven constructs of the world, and by virtue of human judgement, we may value what deserves to be valued.

And say: “Truth has (now) arrived, and Falsehood perished: for Falsehood is (by its nature) bound to perish.”

This observation pertains to our subjective judgement of the world, which informs the subjective nature of our experience of the world. That is to say, value and meaning are seen now not as material qualities that are contained in the physical form, but subject to the judgement of the intellect. Subject to the judgement of the intellect, meaning and value are rooted in the true nature of Being.

And so, while the world of form does not have meaning per se, there is meaning to the world by virtue of Universal Being, which sits behind the appearance of the world. The meaning of the world is in its teleology as per the agency of Universal Being. Agency implies intentionality in relation to acts, that is, there is purpose in why the world exists and proceeds as it does. The only way to apprehend meaning is to imbibe it, and the only way to imbibe it is to connect to Universal Being; it is for one’s Being to move from the level of the particular to the level of the universal. If man searches for meaning in the physicality of the world, he wanders aimlessly as in a desert until he perishes of thirst, never finding except but mirages that evaporate in the heat of his yearning. But if he abandons this wandering in the desert and ventures inside himself, then realization of the meaning of all things occurs, for this is the realm of Truth.

“Do you suppose that you are only a small body, while the macrocosm is placed within you?”

[Attribution] Imam ‘Ali [كرم الله وجهه]

To most of us, what is the world except the people that are most beloved to us? And so the key to detachment lies in the intimate realization of the impermanent nature of your loved ones. It is the most painful realization that challenges us existentially, but being existential, their negation represents the entrance onto the spiritual path. It begins our journey into witnessing the Oneness of God. This is the lesson behind the story of Abraham’s ﷺ symbolic sacrifice of his son, Ishmael ﷺ.

Death is said to be the great clarifier. At once, what is truly important is seen, and what is unimportant is cast aside. The perception of impermanence represents a paradigm shift as a result of a transformation within us that results from intuiting something beyond mere form. As subtle as this intuition is at first, it can have profound consequences. Death is a demonstration that the people we perceive as permanent are ultimately impermanent, and therefore, represent contingent Being. By virtue of contingent Being, death is therefore simultaneously a demonstration of Universal Being, for contingent Being is dependent upon Universal Being for its existence. This is the unifying act because it is to recognize in the particular, in the multiplicity of form, the universality of God. The letting go of form is to travel towards the universalizing light of the heart, which is the seat of consciousness, the throne of God, the luminescent mirror that reflects the ethereal light of the Divine. Cultivation of this paradigm shift is the only way to truly bring to restitution the trauma of witnessing the death of our loved ones, and so their death represents a necessary obstacle for our own maturation process.

Those who, when an affliction visits them, say, ‘Verily we are from unto to Allāh, and verily unto Allāh do we return.’

But how can one do this when it is so painful? If not for the impulses of the ego towards the allure of the world, if not by virtue of compulsive attachments, how can we function as meaningful creatures in the world? But that is the lesson of the Abrahamic sacrifice. It is the willingness to let go of the projections of the lower self and its [base] desire in order to affix the heart to that which is permanent and universal, beyond the flux of impermanence. It is this willingness itself that holds the key to abiding in a state of non-attachment with the world, not the actual physical act itself. That willingness to act is the active force that pierces beyond illusory form and orients the heart towards God because it is an expression of the primordial yearning to once again know God. This yearning is the will to [know] God. This is the true will to meaning. The will to meaning is the will to God. The will to God grants one the willingness to die, and the willingness to die grants one the willingness to abandon [base] desire(s), and therefore, [base] pain(s). And in the willingness to abandon [base] desire and [base] pain, there is the ability to let go of the forms we are so attached to. As far as the subjective character of our experience goes, it is the willingness to forego what you desire most. If you cannot do this, then it tells us something about your inward state. Whatever you cannot forego, you are a slave to, as if trauma bounded. And what you are a slave to other than God, you are imprisoned by; your will, which is meant to be boundless, has become bound in the particularity of physical form.

The masters of the spiritual path describe the different colors of [the stations] of death. There is the white death of fear, pain, and agony of body that comes from the decline of our health; there is the red death of fear, agony, and pain of the psyche that comes from resisting the grip of the ego; there is the black death of fear, pain, and agony of humiliation that comes from social devaluation and rejection; and there is the green death of fear, pain, and agony of the spiritual harm that comes from betrayal. One who has traversed these stages of death is said to become the freest person in the world. An authentic Islamic Tradition is the path of transformation through the stages of death, and therefore, the path to freedom in the transcendence of the Divine.

Has there [not] come upon man a period of time when it was not a thing [even] mentioned, unremembered?

And so, now when meditating upon the Divine Statement, listening to it, absorbing it while simultaneously becoming absorbed in its inner meanings, there is an immensity to it, tinged with a profound sense of grief that is natural to death consciousness. I cannot help but recall my father here, and at once the memories and feelings of that day resurface within me, and my eyes overflow with tears that are filled each with memories of the past and sadness about the future. Indeed, it is as if I am to once again witness his falling away, his letting go into the void. The experience of finding him passed away, the shattering of hope, the sinking of the heart forever, a death experienced. And yet again, another death experienced. The memories of us together from just a few days earlier are still so palpable I can almost expect to see him come home. But juxtaposed against the knowledge of his passing away reveals a ghost. The negation as a meditative practice is to use the intellect to guide the sight of the inner eye to see reality as it really is, and so it is as if you must bear witness to your loved one’s death, to their vanishing, to their departure, again and again, and as many times as it takes to crack your heart open until impermanence is instantiated within you. It is to let their image fall away into the abyss of nothingness, falling into the darkness of oblivion. But that is the true nature of the material world, to be authentic is to accept it deeply. Inauthenticity would be to bury oneself in the busy pursuit of accumulation, but that is the death of the soul.

When we think of a flower, we see its form in our mind. However, that form is a projection of a concept that is imbued with the misperception of self-existence, self-identification, and permanence. It is an image only of its full bloom. And so when we think of a flower, we are really thinking of a [particular] concept that we are attached to, not what it really is. The flower is a process that includes its entire cycle of existence, from the seed all the way up to its full bloom, and then its decay and eventual death, and its dissolution into the soil. The flower also includes the rain and the sun, the nutrients in the soil, and all of the planetary and cosmic forces that lead to its formation. That is the flower, so to see the flower is to apprehend both life and death at once. It is to experience the entire spectrum of contingent Being, which is interdependent in nature. To see independent Being in the flower is a delusion rooted in a materialist ontology. At bottom, God is the First Cause, The Originator, The Creator, The Maintainer, the universal in all particular material causes. And so to see the flower as it really is, is to see the presence of God, both in its arising and in its cessation, and in its very existence.

Just as the flower is the entire chain of its Being, so too are we, so too are our loved ones. When we awaken this level of spiritual vision, then it is as if the people before us are ghosts, and this world is like a dream, for in the encompassing vision of God, all things have already perished. When this is how we see the world, then we abide in a state of non-attachment in relation to it. The knowledge that man was not a thing even mentioned marks the First Principle of its existence. Without this awareness, then we fall into the delusion of permanence and immortality. But to have awareness of it when looking at the world of form is to see with the Light of God. Within esoteric traditions, light is often associated with [Divine] knowledge, which effaces the darkness of ignorance. When this type of knowledge underpins perception to such a degree that the world is interpreted according to it by the intellect, then it is said that a person sees with the Light of God.

“Be in this world as if you were a traveler along a path who feels estranged from the land.”

The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

To see with the Light of God is to awaken the eyes of basira [بصيرة – inner vision]. It is to see that everyone has already died, and all of the hopes and ambitions, the empires and civilizations, all of the objects of envy, have already been reduced to dust. While these insights are demonstrations, proofs, and clarities that result from careful discernment of the world, they are ultimately derived from the experience of inner visions that pierce through the veils of the intellect. Inner vision perceives ma’ani [معاني – pure meaning] whereas basar [باسار – outer vision] perceives receptacles [اواني – awani]. While this world is said to be the world of images that convey meaning, the next world is the world of pure meaning itself. Inner vision apprehends the metaphysical realm, which informs the physical realm.

In a sense, the reason d’etre of Islam and its spiritual path is to tear away the veils, which separate man from God in this world. To see this world fully as it really is, is to see it transparently. To this effect, Imam ‘Ali [كرم الله وجهه] is once reported to have said, “If the veil were lifted my certainty would not be increased.” We might consider this in relation to the narration about the four caliphs, where they each state how they see God in relation to the world. The first three stated that in relation to a thing they see God “with it, before it, and behind it.” Then Imam ‘Ali [كرم الله وجهه] said, “When I see a thing, I see God.” And at bottom, to see with this spiritual vision is the way of harmonizing all forms of human relationships and social dynamics, especially the parent-child dynamic. In relation to the child, this is the penultimate inner state by which the traumas that arise in family systems are brought to restitution.

Inner visions have come to you from your Lord, so whoever sees clearly, it is to the benefit of their own soul, and whoever is blind, it is to the detriment of their own soul.

The letting go of our parents who have passed away is the negation of our illusory concept of them. It is that static image in our mind, that expectation that they will always be here, the perception of permanence, that is being negated. In a sense, we have made their image our home in this life. But this world is not our home, we are meant to be not but travelers passing through. And so this negation, I believe, about negating the childhood image of our parents as those perfect and permanent beings, and instead to see them as receptacles of the Perfect and Permanent Being that is behind their manifestation. By our fitra [فطرة – human nature], our parents represent the Principle of Duality within us as the Masculine and the Feminine Principles that form the edifice of our Being. They represent the traces of Power and Knowledge, the metaphysical realities that underpin all expressed Divine Attributes that make up the world of form. How the child grows up to understand God is therefore largely a reflection of how it experienced its parents during those formative periods of its life. When dysfunctional elements are introduced into the relationship, they cause disruptions in the identity formation process, which causes the parents to become instantiated within the identity of the child as God, almost as a coping mechanism to the fear of abandonment; in this case, notions of God are seen by the child as nothing more than an extension of the parent’s will to control them. But when functional elements are introduced into the relationship dynamic, and the child is able to traverse the developmental stages of the identity formation process, then the parents become increasingly seen as extensions [as in manifestations] of God [God’s Attributes]. In the former dysfunctional case, it is often then that God is seen as an oppressive agent since it was stress in the parent-child dynamic that caused the disruption from which this perception of God arose in the first place. And so by apprehending our parent’s death, by negating our illusory concept projected onto them, by letting go of the particular image of them that we are attached to, we may actually see our parents as they really are. And because of how central our parents are to what we are, it cannot be otherwise that their death represents an important rite of passage along the psycho-spiritual developmental process.

Death is our last testament to the finality of God, but not just the finality, it is also our testament that God is the Originator, for all things that perish are returning to God, and thus first came from God. The end of the spiritual developmental process ends in God, which implies a circular nature to the process of life itself. Life is characterized by a beginning and an end, but the end is the same as the beginning. From the perspective of the material, it is an upward ascent, but from the perspective of the spiritual, it is merely a return. The return to God is the covenant of our existence. To bear witness to it while alive in this world is to fulfill it, and to cultivate it is the spiritual path. Our return to our fitra [فطرة – human nature], our return to God, is intrinsically tied to the return of our loved ones, especially our parents, to God. The path of self-development is not an individual one, but is inherently tied to the concept of community.

And when thy Lord took from the Children of Adam, from their loins, their progeny and made them bear witness concerning themselves, “Am I not your Lord?” they said, “Yes, we bear witness”—lest you should say on the Day of Resurrection, “Truly of this we were heedless.”

In order to bear witness to the Absoluteness of God, contingent creatures have accepted as part of the covenant of their existence to extinguish themselves, for there can be no multiplicity in relation to the universal; nothing can contend with God. Death is the nature of contingent Being. It is the act by which all things other than God are effaced, and thus, the erasure of all notions of duality as the modality into non-duality. Death is to prostrate to God, to seek immortality is to refuse to bow. The acceptance of death is to uphold the covenant, and thus represents the attainment of the will to God through self-effacement. And thus our drive for immortality is rooted in the attempt to violate the covenant of our existence. No doubt, this is the lesson behind the story of Satan’s Deception and Adam’s Fall. That when we seek immortality, we deny death. When we deny death, we lose our sacredness, and when we lose our sacredness, we lose our humanity. We become disharmonious with our fitra [فطرة – human nature], we become distanced from it to the point of denying that there even is a fitra [فطرة – human nature]. And then we fall into suffering.

The soul that is in a state of submission, however, is in a state of harmony with the fitra [فطرة – human nature], its covenant upheld. It hears the command to return, and at once it takes flight like a bird leaving its cage. it leaves behind its physical body without looking back, which is now an empty shell. The body appears to be the same as it was before death, yet at the same time, it is completely unrecognizable as the one who we once knew, like an empty house after our loved ones have departed. It is like a seed that has dried up after the life inside has bloomed into the form in which it was cultivated in the soil of the present life. And thus it is said, death completes a person.

Come both of you willingly or unwillingly.

To witness death is to bear witness to God, for it is God who alone bestows life and who takes it away. Their departure is the prostration of death. And their prostration of death is their negation by which it is affirmed that only God is the Real and Eternal. Our death is the means by which God affirms His Absoluteness, and in that return to God, God’s Oneness. The lifeless body conveys all of that, and thus, it conveys really the miracle of life as something supernatural, meaning that it transcends mere materiality because it [materiality] cannot account for it in the first place. No doubt, this is the wisdom of death in that it highlights so clearly the sacredness of life. Without life, the material world withers away. By witnessing death, we can witness the [immaterial] active force of existence itself as it is withdrawn from the form, and it begins to crumble and vanish. Understanding the sacred nature of life is a part of what it means to see our parents for what they really are, who are thus said to be gates of the Divine Presence itself.

All throughout our lives, our parents took on different forms. They appeared to us one way when we were babies, perhaps as guardian deities; when we were children exploring the world, they appeared as nurturing and protective authority figures; when we entered adulthood, they appeared as complex beings reflecting our own newfound complexity; and when we attained the height of our physical strength, they declined in strength, appearing now as vulnerable human beings, frail yet still strong to our eyes. The eyes of the child rarely see clearly, after all, and as much as we become adults, before our parents we will always remain their children. We refuse to remove its rose tinted glasses, or perhaps we cannot by our own will. But our parents yet appear in another form at the moment of their physical death as the manifested effect that they had on the world and in the very will of those who loved them. And wow clear vision is attained by the child, the tinted glasses torn from its face, shattering to pieces the illusions that reflected upon its lens. Perhaps that is a final gift, a necessary gift, from the parent to the child. This form of theirs, in its invisibility of substance, but visible in effects, represents the transition from the physical to the metaphysical. In this event, there is the effacement of the particularity of contingent Being and the manifestation of the essence of universal Being. The child who learns to see this may now transition also from the particular to the universal, absorbing into his Being the lesson of his parent’s death. It is always a lonely path, but if successful, he can once again see with clear vision the reality of the one they called father and mother in a new form. After all, their forms changed all throughout the stages of life here in this physical world, yet their essence remained. As long as the essence remains, it finds expression through form. This essence is the basis of our sense of the sacredness of life, and it is possible to connect to it through connecting to the essence of the essence of the soul.

So, surely with hardship there is ease.

With hardship there is ease, with pain there is pleasure, with sadness there is happiness, with grief there is joy. The Divine Statement, because it encompasses duality, contains the Principle of “paired opposites”, and thus all particularity. It holds both grief and sadness, as well as joy and hope; the grief and sadness is about the departure of our loved ones, but the joy and hope is from the realization of their being received by al-Waliyy [الْوَلِيُّ – The Friend], al-Wadud [الْوَدُودُ – The Most Loving], and in that reception, there is the permanent and all abiding essence. The grief that comes now with meditating on the Divine Statement is like a door through which we must pass. Being a door, it means that there is somewhere else beyond the door which is other than where we are now. Where we are now defines our perspective, our perspective defines our understanding, and our understanding defines the nature of our experience. In this case, the nature of our experience is rooted in duality. But we must step through that door that lies at the end of the path. The journey through the door of grief is the door of death, and thus represents the journey from duality into non-duality. Grief reveals to us the duality of the Divine Statement, and because duality is the nature of created existence, the Divine Statement is a key that opens for us the secrets of the world. The Divine Statement, like the world, is defined first by the aspect of impermanence, of letting go, and so it is tinged with sadness at the departure of our loved ones. All of us will taste death, all of us will decline and fade away. But beyond the grief, beyond death, there is something else that we are forced to discover through the process of ascension. As we ascend, notions of duality subside, but what that truly means resides beyond the dream, unknown to articulated thought. However, revealed religion challenges us to discover the possibilities that define the true nature of our existence. We can have glimpses of these paradisal realities while alive in this world of veils and illusions, and if cultivated, can give us comfort based not on mere [vain] hope, but on experiential knowledge [gnosis], that is the observation of the inner eye.

“People are asleep. When they die, they will awaken.”

Imam ‘Ali [كرم الله وجهه]

What lies beyond the dream except the dreamer? And who is the dreamer? What are the implications of dying and waking up on the nature of our own Being as conscious beings? The journey of the soul is its transformation, as if the journey itself is a metaphorical story that we are traversing through experience. And so the second aspect of the Divine Statement, the affirmation, is entrance into the infinite realms of the Divine, into non-duality, which effaces all that was before it. The past is gone, absorbed into the infiniteness of memory. And as we awaken to The Real, ascending through the dimensions of reality, the secrets of our longing become revealed to us. In this expansion of consciousness, understanding of what has transpired begins to form, like a puzzle being formed and its shape now more discernible.

To Live – Affirmation of the Divine

إلاَّ اللهُ

Except Allāh [God]

The life of this world, by virtue of death, by virtue of impermanence, is necessarily the mixture of sadness and happiness, tragedy and joy, bitterness and sweetness. As Socrates explains to Protarchus in Phillebus, this world as the third category of existence he calls the mixed life, is an admixture of the first category of existence – the infinite – and the second category of existence – the finite. The mixed life is made up of forms that result from the “weighing down” of the infinite by the finite thereby concretizing [attribution of limit] the abstract as subjective experiences of phenomena by the intellect. This subjective character of experience [of phenomena] as the concretization of the abstract represents the myriad particularizations of the universal within, or rather as, individual consciousness. By virtue of particularity, there is duality. By virtue of duality there are [material] categories of existence. By virtue of [material] categories of existence, there is knowledge by means of comparison. By means of comparison, there is discernment. And by means of discernment, there is individuation. Since the phenomena that make up this world of form as the particular expressions of the universal exists in relation to one another, then as subjective experiences that underpin individuation, we as seemingly separate individuals with separate conscious minds also only exist in relation to each other, made known only by means of physical comparison with each other.

Know that the life of this world is only distraction and amusement, pomp and mutual boasting among you, and rivalry in respect to wealth and children. Its likeness is that of vegetation after rain whereof the growth is pleasing to the tiller; afterwards it dries up and decays, turning yellow, then it is reduced to dust…

This world, by its very nature, is the world of separation by means of comparison. Socrates continues, highlighting that something can only be said to be large in relation to something that is smaller, hot exists only in relation to cold, pain in relation to pleasure, happiness in relation to sadness, strength in relation to weakness, wealth in relation to poverty, success in relation to failure, oppressor in relation to oppressed; things are known by their opposites or what they are not. I am me by virtue of not being you. Despite some yearning to be known, for union, for connection, we are nevertheless driven to assert our [sense of] individuality over others through comparison in order to validate our existence. There then seems to be a contradiction between how we exist, and how we want to exist. This is the conflict between the egoic-self, which is driven to be separate by means of comparison, and the spiritual self, which yearns naturally for Oneness. When we are dominated by the egoic-self, it directs our will to meaning towards further and further individualism, further and further atomization, further and further separation and isolation. And so it is by forgetting death that we forget the interdependent nature phenomena, and thus the interdependent nature of the self. Instead, we attribute permanence, and thus self-existence, to the physical features of individuation. That by identifying with the features of identification, we become immortal thereby taking on the quality of Lordship. But because we are conceptualizing the world now based on false assumption, on misperception, on illusion, the drive to assert ourselves in order to validate our existence is considered as the greatest deceit, which is self-deification. Again, there is that drive for immortality – the Lordship of the ego – the breaking of the covenant of our existence, separation from others, separation from nature.

“Whoever absorbs his heart in love of the world will be entangled by three things: misery that will not cease to discomfort him, greed that will not achieve his independence, and vain hopes that will never reach their end. For the world is seeking and is sought. Whoever seeks the world, the Hereafter will pursue him until death comes to him and it seizes him. Whoever seeks the Hereafter, the world will pursue him until he exhausts his provision from it.”

The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

But beneath the veneer of separation, the world of form – from mental concepts to their associated formal manifestations, which we define the individual self by – are marked by interdependency. As we delve deeper into the fabric of the material world, we see that there is an underlying logic that defines and unifies this world. We understand this logic as manifestations of axioms or First Principles, such as the law of non-contradiction and the law of identity. These Principles, however, merely express the Principle of Duality in its manifestation in the first place, which is thus transcendent to them. And so, as we ascend in consciousness, expanding from the level of the particular to the the level of the universal, delving more deeply into the substratum of existence, into the very ground of Being, we find that the laws that govern the created world(s) become increasingly unified under a singular Principle. And so the Transcendent Principle is known only in relation to the transcendence of consciousness, and thus, through the dissolution of the self as a byproduct of the duality of the material world. We transition from seeing the flower as a static image that conveys self-existence, self-identification, and permanence, to an image that contains the life and death of the entire universe. Within it there is the subtle essence, just as it is also in the body of those who passed away, and apprehended only by the spiritual eyes.

We will [soon] show them [Our] signs of the Divine on the horizon of the universe and within their own souls, until the Truth becomes clear to them. Is this not sufficient as regards your Lord that God is the Witness [ever present] over all things?

This world is meaning set up in forms and images, and so it is an instrument of knowledge. Death is the dissolution of the images of particularity, that is, the physical features of individuation as intermediaries between experience and meaning, which is at bottom what we call the self. And as one ascends in consciousness, as the process of awakening towards The Real, these intermediaries dissolve until they are no more. As the intermediaries dissolve, so too do the forms by which consciousness is individuated. All that remains then, at the end, is the ocean of eternity, the celestial light of God, the world of pure meaning. And this is the symbol of the Abrahamic sacrifice, it was the severing of attachment to the external form thereby apprehending the reality of God that is behind his son, Ishmael ﷺ. The knife was a symbol of the sharpness of the intellect that severed attachment through the apprehension of the illusory nature of form. The altar of sacrifice represented the canvas of the heart, and the form of Ishmael ﷺ represented the idol of the physical world that resided within the heart. This is the premise of the Hajj, our pilgrimage to the Kaaba represents the journey of the soul from its sojourn here in this outer world of form – the abode of provisions – towards the inward transcendental realms of the heart. It is a journey of death as we vanish from the world of illusion and make our long journey home among the throngs of innumerable souls, gathering and traversing the plains of Arafat towards the final abode.

That the final goal is your Lord;

That it is He who makes people laugh and weep;

That it is He who gives life and death

This world, to the spiritual eye, is thus an instrument of knowledge [of God] where by means of comparison with respect to the objects of duality, the knowledge of non-duality may be discerned through the universalizing faculty of the spiritual eye.

The universalizing activity of the spiritual eye [discernment] occurs precisely by effacing particularity as having inherent reality whereby it apprehends the universalizing Principle of existence, which supersedes particularity in terms of what is actual or real. It is to become conscious of God as the universal [true] reality of the particular. The concepts of particularity, and our subjective relationship with them, vanish.

The universalizing Principle of existence is none other than the God Principle, that is, the understanding that instantiates within the heart of one’s Being by seeing God as the essence of all things. Now, when you see a corpse, with the life force already departed, you see al-Mumit [اَلْمُمِيتُ – The Bringer of Death]. When you see a baby born, you see al-Muhyi [الْمُحْيِي – The Giver of Life]. When you see people alive and well, going about in the common movements of the living, you see al-Hayy [الْحَيُّ – The Ever Living]. But beyond all Divine Names is the reality of Allāh. Even when a person dies, even in their empty bodies, there is still Allāh. In every Quality – a Divine Name – as a manifestation of an Attribute, there is found the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God]. As al-Jilli writes, one conceives, then, the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God] through every form (of idea) that flows logically from one of the meanings which It [the Essence] implies. Every Name [أَسْمَاء اللهِ – Name of God] and every Quality [الصافات – Attributes] attaches itself to a subjacent reality which, itself, is its essence. And so, just as all Divine Attributes belong to the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God], all Divine Names that result from the Divine Attributes really belong to God. Just as every Divine Name that results from the Divine Attributes really belong to God, Every Divine Act that results from the Divine Names also really belongs to God. We as the manifestations of those Divine Acts, therefore, belong to God through this ascending chain of Being; in relation to the self, the Divine Acts are its essence; in relation to the Divine Acts, the Divine Names are its essence; in relation to the Divine Names, the Divine Attributes are its essence; in relation to the Divine Attributes, the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God] is their essence. The self, as the manifestation of the Divine Acts, and the heart, as the modality of experience and the seat of consciousness, together make it possible to know Allāh since they are connected to the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God]. And thus it is to this reality that Iblees was instructed to prostrate. The heart exists in between the Divine Attributes and the Divine Acts, and is thus beholds all of the myriad Names of God; its reality is present in both the day and the night, this realm and the next, and on its horizon is the meeting place between both worlds. The infinite knowledge of Allāh is, at bottom, the essence of individual Being discovered when the horizon between both worlds vanishes, and the self is effaced.

Ibada [عبادة – worship]: remember God to re-member yourself.

And so, at bottom, it is God that is behind all contingent Being, the Universal behind the particular, the Abstract behind the concrete, the Transcendent behind the immanent, the Thinker behind thought, the Creator of acts and events and manifestations, the Light behind the eyes of our parents and our children. The One behind the manifestation of the bright cosmos above is the One behind the crawling gnat, and the One behind the manifestation of our loved ones who have passed away. The light has faded from their eyes, but only because the body has perished and the soul called back, but it still shines brightly in the cosmos above and behind the reality of the universe itself. In this realization, as an experience rooted in the perception of inner vision, there is a great sense of relief that seems to be rooted in feeling connected, not physically, but metaphysically. To realize that connection is not physical is to realize that physical death does not sever it. Perhaps then, much of the pain and anguish that is associated with the death of loved ones comes from the perception of severed connection. After all, severed connections with those who are still living are also characterized by anguish and grief, and thus a type of painful death as well. And when this grief becomes permanent, without cessation or end, it transforms into despair. Despair, when allowed to fester in the heart, becomes Nihilism. Such is the death brought on by the poison of unnatural belief, by disbelief.

Do not be like those who forgot Allāh, who by necessity of this were thus made to forget their own souls

The test of life is then a question of whether you are willing to let go of your current perception of reality, which clings to projections and appearances. The test of life is to see the interdependent nature of contingent Being, to let go of all that you, the egoic-self, cling to in order to exist and feel will validate you. And thus, the test is about effacing your self of having inherent reality and entering into a total state of submission before God on an existential level. It is to become reconciled totally with Divine Will, and from this, one attains taqwa [تقوى – God Consciousness] where ego-consciousness dies and is replaced with Divine Consciousness. This is felt as humiliating to the ego because it only exists by means of comparison with others. But when comparison is no more, when [base] desires no longer govern the heart, then the mind becomes still. Only then are we able to see non-duality amidst the painful vicissitudes of duality. This is to see the sacred in the formal, and to treat existent beings with a natural respect and adab [أدب – chivalrous manners] rooted in the sacred nature of Being. This is why, traditionally, knowledge was connected to character; khulukin azeem [خُلُقٍ عَظِيمٍۢ – magnanimous character] is the sign of [true] knowledge and intelligence. The Enlightened Man ﷺ, as the epitome of magnanimity, is thus the direct proof of God through which gnosis is attained. In Islamic cosmogony, Muhammad ﷺ is the instantiation of al-‘aql al-awwal [العقل الاول – The Supreme Spirit] and thus the archetype of creation. We find parallels to this in the other Wisdom Traditions of the world, such as the Buddha-Nature or Atman as the true nature of Mind. The archetype of creation represents the prism through which the Light of the d̲h̲āt [الذات – Essence of God] shines through, refracting it into the myriad Divine Attributes that manifest as the world of form as the Divine Acts. We, as the innumerable beings of the world, are manifestations of the Divine Acts.

I have created neither man nor jinn except to know Me

What all certain experiences of Enlightenment entail is this: The centrality of Oneness, or what in Islam is called Tawhid [توحيد – Oneness]. It demands that all of existence be governed by a single Supreme Reality – which the Chinese ulama had no objection calling by the Neo-Confucian term lǐ [理 – Principle]. Everything comes from this One, Real Principle and everything returns to it. Indeed, the basis of worship is Tawhid [توحيد – Oneness], which literally means “making one” or “making into one”, or as it is sometimes translated into Chinese as “practicing one”. This essential understanding of worship is why monotheism necessarily eschews idolatry, for it is the natural religion, and the nature of the soul is to essentialize, to see the universal in the particular; it is to know Oneness, to see Oneness, to express Oneness, to be Oneness. The soul as an essentializing force returns to Oneness, and in order to return to Oneness, the multiplicity and particularity of contingent Being must be effaced. The world in which we live is thus a journey from the external forms of myriad particularity to the universal Oneness of Being through the process of Ibada [عبادة – worship]. It is the unifying of the fractured mind, withdrawing it from the fragmented existence of attachment to the [base] desires of ephemeral form and returning it to the pure essence of Mind where self-knowledge is known once more.

Whoever knows himself knows his Lord.

[Attribution] The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

This knowledge of God as the Unifying Principle is acquired only through Ibada [عبادة – worship]. It is both subtle yet manifestly apparent because it lies in between the categories of existence. It is the secret path, the middle path that is found in between life and death, existence and non-existence, like a hidden channel between the sun and the moon that leads into the ocean of the spirit realm itself. And thus we vanish from the world. It is the path of the heart, accessed through our internal states that result from our subjective experience of the world of form. As far as the human condition goes, it cannot be otherwise that its entry is through the door of grief, for in the departure from the world there is the profound pain of goodbye. But this grief contains in it the story of our existence, the story of separation from the Divine Presence. And so it is by grief that there can be returning, arriving, and thus, joy; the grief of the human story contains joy, and the joy of the human story contains grief. In one sense, it can be said that the impermanence of the world, by virtue of its ensuing pain, forces us to discover that which is truly permanent and alone capable of making us whole. It is thus the realm of purification, of the gathering of provisions for that long journey home.

O soul at peace. O tranquil soul. Return to your Lord, well pleased with God and well-pleasing to God. Enter with My servants, the holy ones, enter into My Eternal Garden.

The Qur’anic Principle states that when you are pleased to meet Allāh, then God is pleased to meet you. Similarly, when you look forward to meeting God, then God looks forward to meeting you. And when God looks forward to meeting you, then you will become fully realized, like a child who is being gazed at by its beloved parents with the utmost of love. That is the end of goodbyes, for in the meeting with Allāh is the meeting with our loved ones, the lovers of Allāh. That is the end of the spiritual path, this will to God represents the culmination of our will to meaning, for the will to God is the meaning behind our existence in the first place. Ibada [عبادة – worship] is the means of purification by which we efface our delusion, our desire for the illusions of multiplicity that defile the heart and that veil us from our fitra [فطرة – Nature]. By cultivating our connection to our essence, then it is as if we are partaking in the community of souls, participating in the activity of connection. Consciousness is indeed mysterious, the assumption of its end at physical death is a veil.

You will be with those whom you love

The Messenger of Allāh ﷺ

And thus it is said that death is the precious gift to the Believer. It is that which removes the veils of separation that stand between the lover and the Beloved. In this understanding there is indeed relief because the connection remains intact, unsevered. When the connection remains, then death does not feel like the end. This gives us the spiritual endurance and the psychological resilience to bear the weight of the world and its trials and tribulations with beautiful patience and gratitude. Bearing this weight with the light of [true] knowledge, belief transforms into certainty, and with certainty, we strengthen our hearts. This ability to continuously strengthen the heart is what reveals to us the true potential of the human spirit. Natural belief is therefore necessary for the spirit to grow and mature in proximity to God, which occurs by virtue of this very living connection. Our strengthening comes from being connected, like a lifeline. It does not occur on its own, and this is the metaphysical basis of a Living Tradition. God is the One who so lovingly holds so closely our luminescent ancestors, all gathered together in the community of souls, surrounded perpetually by the lovers of God. While this is the world of meaning setup in images, the next is the world of pure meaning; here we search for love in images, there we simply abide in love, such is the nature of connection.

Mevlana Rumi [رَضِيَ ٱللَّٰهُ عَنْهُ] describes the hadith of death:

O Generous Ones,

Die before you die,

even as I have died before death

and brought this reminder from Beyond.

Become the resurrection of the spirit

so you may experience the resurrection.

This becoming is necessary

for seeing and knowing

the real nature of anything.

Until you become it,

you will not know it completely,

whether it be light or darkness.

If you become Reason,

you will know Reason perfectly.

If you become Love,

you will know Love’s flaming wick.

[Extra] References

[1] Of the Essence: Universal Man, by ‘Abd al-Karim Jili: Chapter 1

[2] Chinese Gleams of Sufi Light: Wang Tai-yu’s Great Learning of the Pure and Real and Liu Chih’s Displaying the Concealment of the Real Realm. With a New Translation of Jami’s Lawa’ih from the Persian by William C. Chittick

[3] Ali ibn Abi Talib and Sufism: Caner K. Dagli

[4] Zaynab Academy: Understanding the Three Stages of the Nafs

[6] Wikipedia – Nafs

[7] Sufiwiki

Comments by emptyingthecup

Sahasrāra – The Crown Chakra

"Bismillah, forgive me for the delayed response. Thank..."

The Paradigm Shift of Confronting Shame with Gratitude – Reversing the Spell of Māra

"Hi Luis, I apologize for the late response. As a first..."

A Meditation on the House of the Heart by Rumi

"Hi Luis, you're welcome. It's good that you're hesitant to..."

The Pain of the Heart is the Path Towards The Divine

"Thanks for the comment. As with any phenomenon related to..."

The Pain of the Heart is the Path Towards The Divine

"It is because we are not our identities. Identities are..."